Sharing Indigenous Cooking Traditions in New Mexico

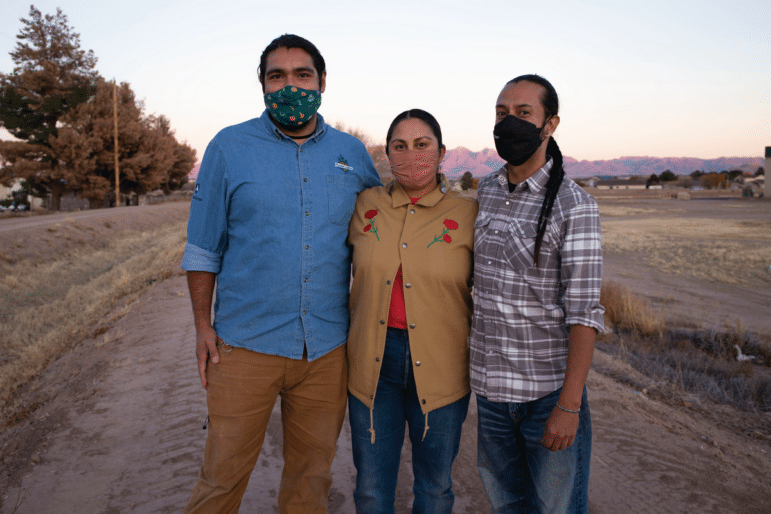

Through Magia de Maíz, FoodCorps service member Luis Ramos and local chef Mateo Herrera teach students about Indigenous food traditions.

Join our corps! Applications for 2026-2027 are now open. Apply by March 30.

Through Magia de Maíz, FoodCorps service member Luis Ramos and local chef Mateo Herrera teach students about Indigenous food traditions.

In Las Cruces, New Mexico, a school community is cooking up cultural connections.

FoodCorps service member Luis Ramos and local chef Mateo Herrera have partnered to teach students at Raices del Saber Xinachtli Community School about Indigenous food traditions, focusing on corn. The place we call Las Cruces today — originally known as Moy-tu-he-hém — is the ancestral land of the Piro-Manso-Tiwa peoples, among others.

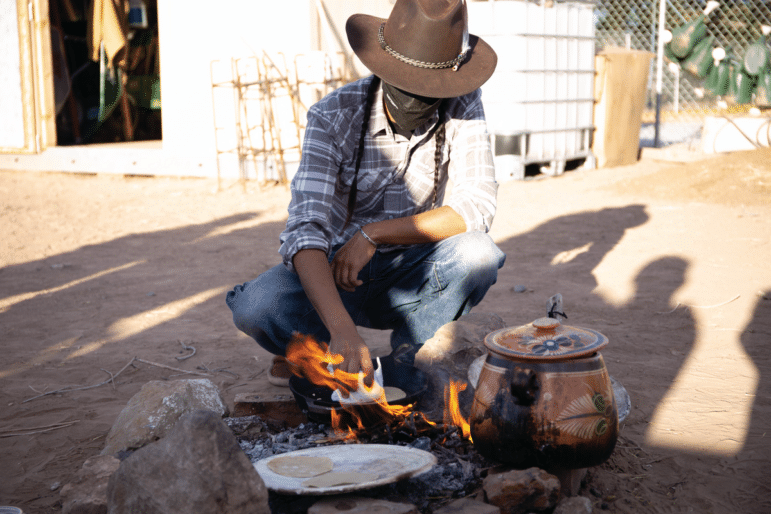

Twice a week, Luis and Mateo lead an after-school program, Magia de Maíz — “the magic of corn” — for the second and third graders. Together they prepare a variety of corn over a fire, teaching the kids about the cultural significance of the ingredient.

“Every class, we have a little ceremony. We have the fire going, gather around it, and talk about these foods, specifically about corn, how it relates to every aspect of our life,” Mateo says. “Using that plant in general opens up so many ways to teach about nutrition, food history, and farming. It’s so deeply rooted in every culture in the southwest.”

Raices del Saber Xinachtli Community School serves about 90 students total, and between 15 and 20 participate in Magia de Maíz each week. Luis uses the program to teach hands-on lessons about corn, like how to grind corn by hand to make masa for tamales.

“It’s really hands-on for the kids,” Luis says. “All the ancestral practices that go along with corn are really enlightening.”

Anita Lara, the school’s OST coordinator and a FoodCorps alum, tells a story about how the students are making connections between traditional practices and more modern foods.

“The other day in the garden during a class, they ground a bunch of corn to make tamales, and the following Thursday Mateo brought in chocolate tamales. When they opened them up, one of the kids goes, ‘It’s an ancient brownie!’ The whole rest of the day they were like, ‘Who wants an ancient brownie?’ It’s wonderful to see the connections between the contemporary and the traditional, the past and the present, those connections they make.”

The school garden is set up in the traditional manner of the medicine wheel, known as the Nauhi Ollin in the Indigenous language of Nahuatl, with a large circle divided into four spaces facing each of the cardinal directions. The group has also discussed building an horno, a traditional oven made out of earth. Luis and the students water everything by hand, and they get to taste the fruits of their labor, too.

“Some of the students have little experience with maíz; they don’t realize there’s blue corn, purple corn, they were all amazed at the different types,” Luis says. “Especially for kids who are first-generation American, who speak predominantly Spanish at home, it’s bringing them closer to home with these dishes that are very old and used in the culture around here traditionally.”

Luis and Mateo say they’re looking forward to planting season. This spring, the adults and students will plant different varieties of corn, as well as native bean and squash plants for a three sisters garden. Together, they’re growing ways for students to connect to their heritage, their ancestors, and their community.

“What they’re taking home most of all is memories and connecting,” Mateo says. “We lost a lot of foods and traditions; we’re losing our elders; a lot of their children didn’t pick up those recipes and continue on in those traditions. For me that is more important than connecting them to history. This is the stuff that’s going to change their life around. It’s that connection to the memories, to the heart. And every one of them has connected in some way.”

Mindful Tasting: Eating with All 5 Senses

Our 2025 Child Nutrition Policy Year in Review

Winterizing Your School Garden