Cultivating Belonging in Ourselves and Our Communities

How magic moments are made through inclusive education and relationship gardening.

How magic moments are made through inclusive education and relationship gardening.

This piece was written by Ren Driscoll, FoodCorps Michigan Service Member ‘21-’23, and shared at this year’s Mid-Year Gathering for service members.

If you know me, and I asked you what my favorite part of being a service member is, you’d probably shout out answers like educating folks about food sovereignty, or teaching about the relationships between local food, the environment, and a regenerative economy.

While I certainly love these things, you’d be wrong. My all-time favorite part of my role is cultivating a sense of belonging.

In the Michigan school where I serve, I have found a sense of belonging more so than with some friends. More so than with some family members. And sometimes, more so than even within myself.

I’ve witnessed one of my favorite teachers do everything she can to make sure a student named Eli, who uses a wheelchair, is included in every outdoor activity we do, pulling him in a sled through the woods for sugarbush and working with us to make a garden bed that is waist-height so he can grow food too.

When I came out to a group of my students last year, telling them that I actually don’t identify as a girl or a boy, Norman, an intelligent and earth-loving kindergartner, excitedly exclaimed, “I know what that means, you’re nonbinary! I thought I remembered you said you use they/them pronouns too.”

But my favorite moment of belonging was in November during a Native American Heritage Month lesson. I stood in the classroom with Meghan and Courtney, my service site’s food education service members, discussing the Anishinaabe story of the Three Sisters, the importance of this month and this food, and the agroecological and nutritional benefits of these powerful sisters.

This was our first lesson of the year focusing on Indigenous foodways. As we asked students what they already knew, a slew of eager smiles crossed their faces. They waved their hands in the air, sharing that they’re Native, how jazzed they are for this lesson, and that they eat this food at home!

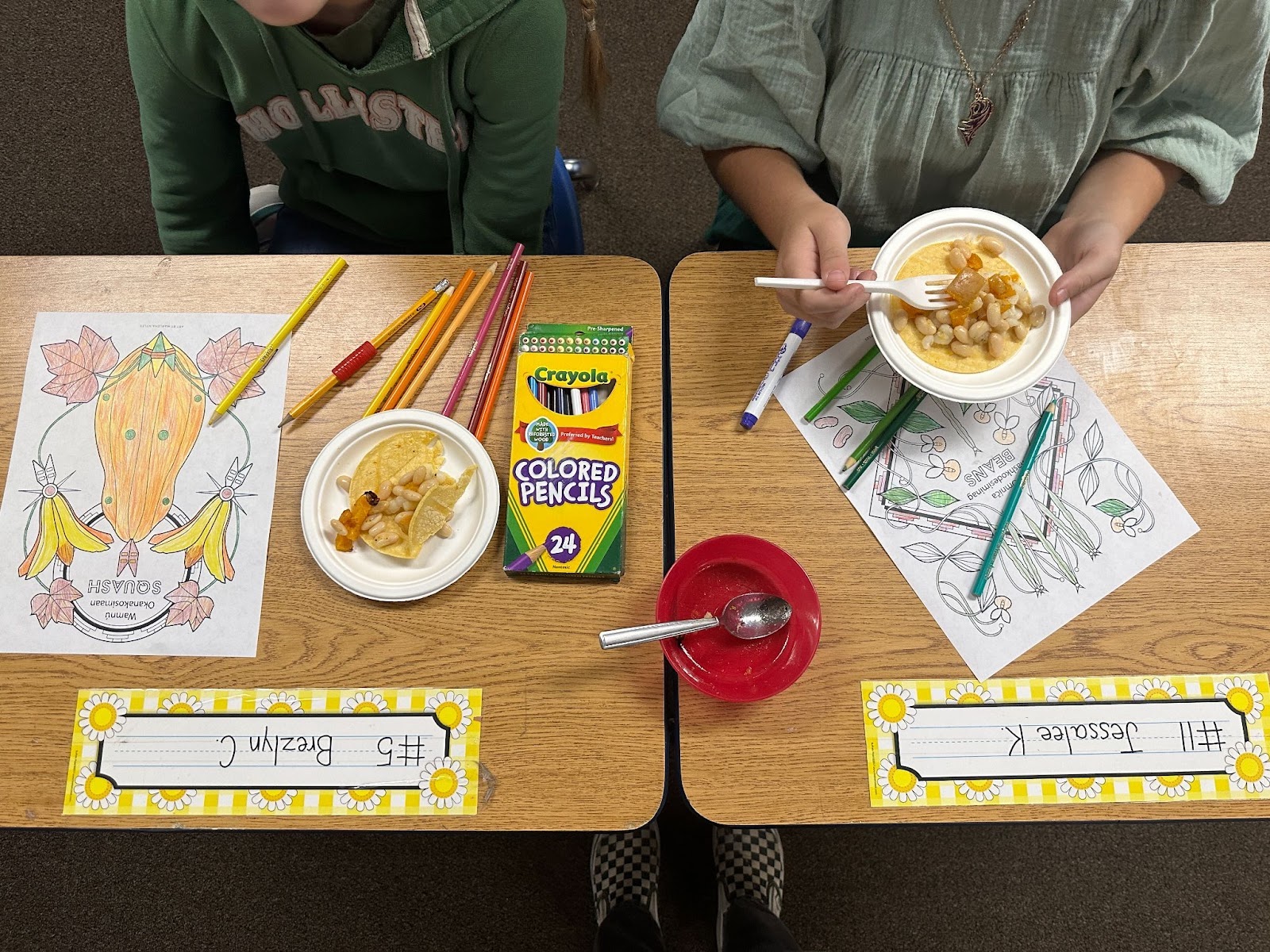

While Meghan and Courtney fried the corn tortillas, the hominy, the great northern beans, and the local squash, I passed out beautiful coloring pages of the three sisters that were sent to us from the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians. They were adorned with words and phrases in Anishinaabemowin, the Native language local to our area, along with flowers, vines, and intricate designs.

As I walked around the class, I noticed that Aniya, the student who was most excited, had colored her okosimaan, or squash, in rainbow colors. She turned to me and said, “Look! I made a Native pride drawing! This should be our flag.”

I bubbled up with excitement, “That would be an incredible flag! But here, let me show you something.” I ran over, grabbing my still-warm coffee cup, and showed her my Two Spirit flag sticker — representing some Indigenous people whose experience of gender expands beyond the binary — that I bought from an Anishinaabe artist named queerkwe.

“This is the Two Spirit flag, it’s a version of a Native pride flag. The sticker is made to look like it’s beaded. Isn’t it beautiful?”

She outwardly gasped, “Oh my gosh! I love that! I think my mom has that flag somewhere!”

I saw her the next day as I was helping fill the salad bar with local carrots. She ran up to me and said, “After your lesson, we’re focusing on tribes in our class. I got to pick my family’s tribe, and do a project about the history and meaning of my tribe.”

I smiled and replied, “That’s amazing! I can’t wait to see your finished project! Enjoy your lunch!”

Moments like these bring me back to my own history, my own belonging in schools. My childhood didn’t include the same teachings about Indigenous peoples, lessons highlighting diversities of identities or experiences, or social and emotional learning. But I do remember the sense of belonging I felt, and that I’ve since carried with me, because of my fifth grade teacher.

While this teacher was quiet about her personal life, one time after school we were discussing her pets, and she showed me a picture of herself with her partner on a hike. Her partner was a woman.

I had never before met an out queer person in my life. I felt like I had gone from living in clouds throughout the winter to seeing a blue-skied, sunshine-y day. We discussed our love for animals and the planet, and she told me she was a vegetarian.

That day I learned two ways of being that I didn’t know possible; two ways of loving that I didn’t know possible.

Throughout each school day, we have interactions with many students that slip off the tongue and dance out of our memories. A smile, a joke, a hug. It’s hard to remember it all between the thousands of taste test bites and endless flecks of dirt under our fingertips from digging in school garden beds. But it’s within those moments that you, as a service member, are changing lives.

My fifth grade teacher, to my knowledge, has no idea of the profound effect she had on my life. I went from a closeted, quiet child to a proud, queer human who isn’t afraid to take up space. I’ve also been a vegetarian ever since.

Maybe someday Aniya will look back at me, like I look back at my fifth grade teacher, and see a role model. Maybe Eli will look back at Mrs. Kerr as the teacher who knew that he could do anything. Maybe Norman will look back at his time in kindergarten and see that his unconditional acceptance was not only affirming but world-changing.

On your tough days, when your skin is sunburnt from hours outside at your school garden or when your hands are sore from cutting hundreds of carrots, remember that you are a holder of magic moments.

The magic in these moments is that they’re not always visible to us. But I promise you – they are there in the hearts of our students, in the experiences of our schools, and in the memories of our communities.

Our 2024 Child Nutrition Policy Year in Review

9 Thoughtful Holiday Gifts Made by FoodCorps Alumni

The Policy Brief, Fall 2024: After the Election